HIGH-LEVEL RISK MANAGEMENT

THE GLOBAL CONTEXT

The

discussion in the media continues to focus on the movement of Russian troops in

the vicinity of Ukraine and the possible invasion of Ukraine it may prepare, as

well as on the sanctions against Russia this would produce. The December 30th

diplomatic discussions between Presidents Biden and Putin seem to have focused

much more on the matter of long-term security arrangements between the US/NATO

and Russia. The media focus on possible war rather than on possible peace keeps

the pressure on both sides to continue their discussion. This is important

especially for the US as there is probably neither a full understanding of

President Biden’s objectives nor full domestic or Euro-Atlantic support for the

negotiation process he has agreed to initiate with Russia. That process is

predicated on the pursuit of long-term objectives that may not be shared by the

US foreign policy establishment or by the countries of the so-called New Europe

such as Poland and the Baltic States. Some, even within the Biden

administration, would rather continue the policy of confrontation with Russia

and would object to anything that appears to reward rather than punish Russia.

Ever since

the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty ceased to be operational in July 2007

there has not been an arrangement that would define the terms of acceptable

military presence between Russia and, for all intents and purposes, the rest of

Europe. More recently, with the US withdrawal from the Intermediate Range

Nuclear Forces Treaty in August 2019, there has also been no framework for the

control of nuclear missiles in the European theater of operations.

There have

of course been attempts to fill the void, including the short-lived proposals

for a new European security architecture by then President Medvedev in June 2008.

Since then, with the war in Georgia in August 2008 and the conflict over Crimea

and Eastern Ukraine in 2014, the circumstances have not been conducive to

discussions on that theme. New START, the US-Russian treaty that limits the

number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads was, however, extended in 2021

for another five years.

What also

has become clear to Vladimir Putin the course of last year is that tension can

be creative. The movement of Russian troops closer to the Ukrainian border in

early 2021 fulfilled its expected purpose. The Ukrainian side got the message

that the Donbass was not going to be regained through military means. Bringing

the troops back to the Ukrainian border might create the tension that would

trigger US appetite for wide-ranging security discussions that have not really

happened for many years.

Under the

pressure of possible war in Ukraine, what Presidents Biden and Putin have

agreed to do is to start working on a new broad long-term security arrangement that would deal with the new alignment of forces in Europe. This is what Russia essentially proposed as early as in 2008. In the context of an ever-expanding NATO, the US did not see this as a priority, but may be willing to consider it now as a way to ensure stability while reducing its own military presence in Europe. On a personal note, Biden is old

enough, literally, to have been a first-row witness of all the major disarmament

treaties that were signed with the Soviet Union beginning with START in 1971.

He would be partial to that type of arrangement that could lessen the tension

between the US and Russia. Nowadays he would fully appreciate the fact that

this would allow him to focus more energy and attention to dealing with the

China threat. It might not detach Russia from China but would lessen the

prospect of a closer alliance between the two. Vladimir Putin publicising his

briefing of Chinese President after his conversation with Joe Biden was both a

reminder to Biden of what is at risk and to China that nothing will be done

behind its back.

As for Canada,

it would find it difficult not to support the Biden approach, but it may need

to produce a creative way of reconciling its unconditional support for Ukraine

with a process that appears to give less importance to the specific

Ukraine-Russia conflict.

--o--

THE UKRAINIAN CONTEXT

|

| President Zelenskyy, NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg NATO Headquarters, December 16th ©President of Ukraine Website |

What has

become clear to Russia in the past few months is that there is a threat of some

ersatz NATO membership for Ukraine in the form of a bilateral military

partnership between the US and Ukraine. The flood gates of NATO membership may

not open for Ukraine, but there could a creeping growth of US military presence

on Ukrainian territory in the form of increasingly more sophisticated military

equipment, well beyond Turkish drones and US Javelin missiles.

Joe Biden’s

acquiescence to the idea of security discussions with Russia may also be

consistent with his approach to the conflict in Afghanistan. The US should not extend

its presence or commitment in a case when no resolution is in in sight. Afgnanistan returned to the Taliban, but Ukraine will not return to Russia.

The

acquiescence to the discussions is also an indirect but clear acknowledgement

that the situation in Ukraine will not be resolved shortly and that, in any

event, it is not for Russia to make the next move. One should not expect that

this would be well received in Ukraine. This is not to say that the US will

stop supporting Ukraine or that the broad question of European security can eventually

be resolved without the specific question of Ukraine being resolved or at least

frozen in some acceptable way. It does however put some pressure on President

Zelenskyy if he wants to avert the risk of Ukraine’s lost territory becoming a

Cyprus-like frozen conflict.

Despite all

the care that the Biden administration has taken to assuage Ukrainian concerns,

it was only a matter of time before a political commentator would suggest that

Biden is betraying Ukraine. Ironically, it is Andrey Illarionov, a Russian

national, a former advisor of Vladimir Putin and one of his most vocal critics

who did it, in unequivocal terms: “Biden once again surrendered Ukraine. On all

issues that matter to her, he completely sided with Putin.”

The Kremlin

readout of the most recent Biden-Putin meeting also notes that President Biden

offered assurances that the US does not intend to deploy offensive weapons on

the territory of Ukraine. That would held clear the atmosphere of the upcoming US-Russia

negotiations but would once more disappoint the more hawkish elements in the US

and Ukraine.

What is not

covered thus far is what the US proposes to do with the Ukraine-Russia

confrontation. There is still an interest in resolving that conflict. There is

now a new truce in place in the Donbass area. It may last longer than previous

ones. Reducing militarisation in that region first might be a first step that

fits in the resolution of the global conflict. In order to enable Zelenskyy to

engage credibly in any peace discussions, he has to be seen as having gained a

stronger position both at home and vis-à-vis Russia. This is a tall order. A

complete cease-fire, the withdrawal of some Russian troops and possibly the commitment

to the presence of neutral peacekeepers might help.

--o--

THE NEGOTIATION

The Russian

idea of publicising the draft texts of treaty with the US and with NATO may

have appeared as rather unusual. The fact is that this is a negotiation that

will have to be transparent in any event given the number of participants and

the expected reluctance in some NATO quarters. Ultimately, public discussion

could facilitate the work of the leaders. Including a clause that would

preclude further eastward expansion of NATO (mostly Ukraine) allows all the

NATO spokespersons to posture and repeat their mantras about the unacceptability

of Russia deciding for NATO. As noted above, Presidents Biden and Putin already

know that Ukraine will not become a member of NATO in the near future. They

also know that an outright exclusion of NATO membership will never pass.

Renouncing that exclusion can, however, be presented as a Russian concession

whenever appropriate. In any event the real goal is to prevent NATO assets (missiles

and troops) from being too numerous and too close to Russia and equally for

Russian assets to be in comparable number and distance from all NATO countries

and NATO-aspiring countries.

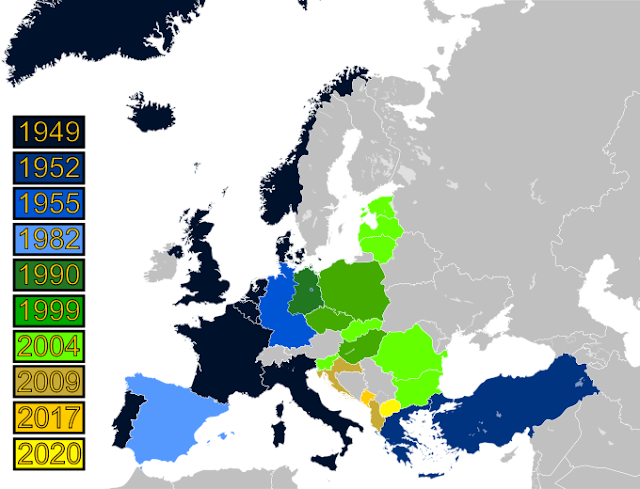

|

| Evolution of NATO in Europe ©Patrick Neil |

It has been observed that the staging of NATO missiles in the proximity of Russia would be as unacceptable to Russia as the staging of Soviet missiles on Cuba was unacceptable to the US in 1962. This gives a good sense of what has to be negotiated first. It should also be noted the deployment of US missiles is what is at stake, not any British or French ones, and that this would be exclusively a US decision no matter how much the Ukrainians may want them on their territory.

Finally, the staging of the upcoming discussions (US-Russia on January 10th, NATO-Russia on January12th and OSCE on January 13th) may not guarantee success but suggests that the process is carefully choreographed.UKRAINE: SCRAMBLING FOR SOLUTIONS

At a time when

the need for a strong president is felt more acutely, it looks as though President

Zelenskyy has reached his lowest popularity level. His attempts to buttress his

nationalist credentials with some anti-Russia trade measures or to appear as a

strong leader by allowing for the prosecution of his predecessor, former

President Poroshenko, are unlikely to have much positive effect. Zelenskyy is

of course coming under all forms of attack from political adversaries but also

receives the occasional indirect criticism from the US Embassy for, as an

example, the appointment of a key anticorruption official.

|

| President Zelenskyy visiting the Donbass frontlines, December 6th ©President of Ukraine Website |

The latest

attack from a former Interior Minister is that the Putin administration disposes

of compromising material against Zelenskyy. That would seem far-fetched but is

revealing of the current atmosphere.

The fact that

Zelenskyy was perhaps the only leader not to have received New Year’s greetings

from Vladimir Putin would normally have been a badge of honour but seems to

have had no positive effect on Zelenskyy’s standing. More timely calls from Joe

Biden would probably have been useful. In the context of the current US-Russia conversations,

the question remains as to whether Zelenskyy is part of the problem or can

become part of the solution.

--o--

MEMORIAL, THE SAKHAROV LEGACY

Memorial,

the human rights NGO whose work includes researching and keeping the memory of

past repressions in the USSR and current repression in Russia, was shut down on

December 28th by a decision of the Russian Supreme Court. That decision can be

explained in legal terms on account of the restrictive Russian legislation on

foreign agents. The decision to prosecute may not have been only based on an

attempt to deny the repression of the Stalin era but as well to quell a

dissenting voice in the interpretation of historical and current events. The

nuance is important in the context of a society that no longer has the likes of

Andrey Sakharov and, as a result, has few widely respected and authoritative

dissenting voices.

--o--

No comments:

Post a Comment