BRETON/GEROL NEWSLETTER

The Breton/Gerol newsletter (BGN) is aimed at partially filling the vacuum of knowledge, understanding and realistic analysis of the events in Russia, Eurasian Economic Union and Eastern Europe that has developed in the last two decades

Thursday, February 24, 2022

Friday, February 4, 2022

ISSUE 60

THE BRETON/GEROL NEWSLETTER

POSSIBLE SCENARIOS FOR A SHADOW THEATER

For another

month public discussion continues to focus on a possible Russian invasion of

Ukraine. The US and Russia also continue to blow hot and cold about the

prospects of a global discussion on European security, showing no sign of

satisfaction over recent exchanges, but leaving the door open to further

negotiations. A lot of time is still spent trying to offer a plausible answer

as to what President Putin’s real intentions may be and to what Russia will do.

|

| Secretary of State Blinken, Foreign Minister Lavrov Geneva, January 21st, ©RFE/RL |

In simple

terms, Putin’s foreign policy is essentially based on the principle of

advancing Russia’s interest. Whichever way you look at it, the invasion of

Ukraine would not serve these interests. Au contraire, it would

seriously damage Russia’s interests. The warnings of everyone from President Joe

Biden to Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly that Russia would face the heaviest

consequences if it invaded Ukraine are unavoidable political statements, but

they do not tell Putin anything he does not already know.

Many

observers seem to have forgotten already that Putin has stated his position

clearly before Russia’s foreign policy establishment on November 18th.

Simply put again, Putin stated that “tensions are useful and will be maintained

for as long as deemed necessary, but there will be no new conflict.” No matter whether you are ready or not to

believe Putin, this is what has happened since November. Carnegie Moscow

Centre’s Alexander Baunov has coined the formula that likely best describes

Russia’s position and the US/NATO response: “In its negotiations with the West,

Russia is behaving not like a country preparing to wage war, but like a country

that, if necessary, can afford to do so. The aim of the West, on the other

hand, is to avoid war. Consequently, Russia can exploit Western fears of

war—without actually using force.”

In agreeing to have his senior officials discuss with their Russian counterparts the idea of new arrangements for European security, President Biden has also made clear his intention to engage with Russia, even though he has in public kept emphasising that he is warning Russia not to invade Ukraine or else pay a huge economic and political price for it. In one of his impromptu press events, he clarified that there were areas (missiles and deployment of troops) where negotiations would be possible and desirable. It is also clear, however, that the US position does not include a discussion about the indivisibility of security. That is essentially the idea that States will not strengthen their security at the expense of other States. This in the Russia view is what should condition the reach and possible expansion of NATO.

The

fundamental incompatibility of US and Russian views over the scope of the

security discussions should mean there is little point in continuing, unless

the Russian side is willing to accept that the scope will be limited to

disarmament and confidence-building measures. For Russia, this would still be meaningful

but would imply settling for less than originally requested. That decision

essentially rests with Putin. He, however, would have known very well that the

US would never agree to the principle of not allowing Ukraine into NATO. He

also knows from US statements that Ukraine is not expected to be a member of

NATO for at least ten years.

Whereas we

know pretty well Putin’s intentions and his ideal objectives, we can only

speculate about his bottom line. Even though Russia initially insisted on a

quick launch of the negotiating process we also know that in comparison to NATO

counterparts Putin is in no rush and can live with the tensions he has created.

The recent announcement of selective and relatively symbolic reinforcement of

the NATO military presence in Eastern Europe was obviously not well received in

Moscow, but it does not amount to a real increase in the threat level for

Russia. What is not certain is what specific steps Putin might take, short of

starting a new conflict.

At the

right time for him and in the right circumstances, Putin could still decide to decide

to take up the US/NATO offer to re-launch European security discussions. Beyond

that, there are essentially two major options, The first one is to continue

working at getting NATO on the road to producing some reduced version of the

full security guarantees that were requested, knowing well that this is an

uncertain long-term process. This would imply working directly on individual

European members of NATO and especially on the weaker links in the NATO chain. It

is worth noting in this respect that President Putin just hosted Prime Minister

Orban of Hungary and has accepted President Erdogan’s invitation to visit

Turkey in the near future.

The second

option is to close the books for the foreseeable future on any accommodation

with NATO and, invoking NATO’s refusal to negotiate the important issues, firm

up Russia’s security position in various ways some of which may be

irreversible. There is already serious speculation about this including, for

instance, the recognition of the independence of the rebel regions of Eastern

Ukraine or upgrading the military presence in Belarus. That could also include

the actual deployment of new weapons systems.

Having

launched the current process, President Putin has to end it up with a win or,

as a minimum, a face-saving exit. He, however, controls the timeline and in the

meantime can keep the negotiation going and the other side guessing. In this

case, President Zelenskky may be offering the best advice by calling on the

West not to encourage panic.

--o--

OBSERVATIONS ON BRIEFING YOUR FRIENDS, GETTING YOUR STORY STRAIGHT AND USING A CRISIS

The Biden

administration’s early response to the unusual presence of Russian troops was

evidently first conveyed through official channels. It did not take long for

detailed information about Russian troop movements to be made public through

intelligence leaks via credible entities. Whether this was intentional, and

part of a plan will be evident later. What matters is the result. Once

intelligence about Russian actions becomes public the administration has no

choice but to adopt a very tough stance, not asking Russia to move its troops

but threatening Russia with the direst consequences should it proceed with an

invasion. Paradoxically, the heightened tension that Russia has vowed to create

provides the US side with the right context to overcome its reluctance to

engage in security discussions with Russia. What raises questions is the fact

that there seems to have been a situation where the intelligence was leaked

before it was properly shared with all relevant Ukrainian security officials in

the early days of the crisis. Pronouncements first by Foreign Minister Kuleba

and then by President Zelenskyy himself also suggest that the US did not

convince all its Ukrainian interlocutors of the severity of the Russian threat in

the same manner as the impression was created in Western media.

|

Armed personnel carriers 35 kilometers from the Ukrainian border, January 19th |

The

Ukrainian side can explain away its lesser concern about the Russian threat by

the fact that it is already at war with Russia for many years. It remains that

even the problematic discussions between the US and Russia about European

security actually downgrade the priority that Ukrainians would like to give to

their own question. There have already been rumours about difficult discussions

recently between Presidents Biden and Zelenskyy. Zelenskky also publicly

criticized the US for removing non-essential staff from its Embassy in Kyiv. Canada

also removed it non-essential staff from its Embassy.

In late

January, the UK authorities released intelligence suggesting that in addition

to threatening war on Ukraine, Russia was planning to install a puppet régime

in Kyiv. Names were named and details were given. The whole idea has so little

plausibility that it soon was forgotten. Russia trying to do this now does not

make a lot of sense. Ukraine accepting it is even less plausible and is close

to being an insult to Ukrainian democracy. There may still be room for

improvement in Ukraine, but a puppet régime would nowadays not stand a chance.

Not long

after the UK story, major US networks cited senior US officials claiming Russia

had moved blood supplies close to the border, indicating a potential imminent

military attack. Ukraine’s deputy defence minister, Hanna Maliar, subsequently denounced

the blood supply claim, calling it a provocation designed “to spread panic and

fear in our society.” Maliar added: “It simply wasn’t true. We found no

information to back this up, we did not see any blood supplies moved to the

front or even in the civilian hospitals around the front.”

Commentators

occasionally observe that unpopular leaders will resort to war to boost their

rating. Reputable polls still place Vladimir Putin above the 60% mark. As noted

above, he said himself “no new conflict is needed.” The threat of war can

however be used as well by those who do not intend to wage war but can

nevertheless illustrate themselves at preventing it.

The beleaguered

UK Prime Minister attempted to present himself as the strongest NATO leader in

the confrontation with Russia. For good measure, Prime Minister Johnson then

added a visit to Kyiv. He eventually also put in a call to Vladimir Putin. Changing

the British newspapers' headlines for a few days may ultimately not help Johnson survive

a leadership crisis, but it offered a welcome reprieve.

|

| PM Johnson and President Zelenskyy on the grounds of St.Sofia cathedral Kyiv, February 1st © President of Ukraine Website |

French

President Emmanuel Macron also tried to use the Ukraine crisis to bolster his

ratings in preparation for the upcoming election in which he is seeking a

second mandate. Adopting a very different approach and taking advantage of his

warm relationship with Putin (he refers to him on a first name basis and seems

to address him with the familiar “tu”) he called him twice in a couple of days

and seems intent on maintaining an active conversation with Vladimir.

The

activity of the British and French leaders makes the absence of the new German

leader even more conspicuous. After one of his military commanders commented that

Crimea would never return to Ukraine, he may have wanted to keep a low profile

but will soon join the group of leaders calling the Kremlin. Olaf Scholtz may

have to address the thorny issue of energy sanctions against Russia that others

are contemplating but that would affect Germany most directly.

--o--

MINSK PLUS?

In the US

response to the Russian proposal for security guarantees the part that deals

with Ukraine refers to the resolution of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine “on the

basis of” the Minsk Agreements. Around the same time a senior Ukrainian

security official has openly spoken against the implementation of these

agreements. The wording thus seems to confirm a slight shift of emphasis from what

was said before. The US publicly continues to call on Russia to implement the

Minsk Agreements, but in what was supposed to be a confidential document it uses a

form of words suggesting that the Minsk Agreements are a guide rather than the

final word.

Foreign Minister Kuleba later issued a statement to the effect that a special status for the Donbass area is unacceptable. Such a distinct status is a key provision of the Minsk Agreements. This essentially confirms the impossibility of implementing the Agreements in their present form.

Although

some Russian observers keep asking whether the US will eventually pressure

Ukraine to move along, there is little likelihood that this would ever happen. In what amounts to a constitutional matter, the US has no inclination or interest in pushing Ukraine and will not try. US Under Secretary of State Nuland

even claimed on a Moscow radio station never to have heard directly from the

Ukrainians that they had a problem with the Minsk Agreements. In dealing with

the Minsk Agreements the key challenge remains to come up with an improved arrangement

that is acceptable to the vast majority of the Ukrainian political class and

that still would have some appeal to Russia and the rebel regions. This may

well require focussing first on security arrangements that could bring back a form

of normalcy to life in Eastern Ukraine and to relations between that region and

the rest of Ukraine. Mediation by a country that is perceived as a true neutral

player may be a solution. Turkish President Erdogan just visited Ukraine. He keeps

offering mediation efforts. Turkey though may not be the right country and

Erdogan not the right leader at this time.

|

| Presidents Erdogan and Zelenskyy, Kyiv, February 3rd ©President of Ukraine Website |

In the meantime, there is nevertheless in parallel a continuing conversation among Normandy Four officials about the way ahead in the implementation of the Minsk Peace Accords. There is still a need to firm up the cease-fire arrangements that would facilitate more global security discussions and might lead to a reduction of tensions on the Ukraine-Russia border. The telling comment from the lead Russian negotiator about the most recent meeting was “there is nothing to brag about here.” The Ukrainian president’s office had a much more upbeat assessment. It looks as though there was progress in process more than in substance.

--o--

WEAPONS AND TROOPS FOR UKRAINE?

There has been considerable debate in Canada about the provision of lethal weapons to Ukraine. The Canadian government claims it has received no such direct request from the Ukrainian government. Others claim it has, at least in Canada, and that there is an obligation to respond favourably. It would indeed be consistent with Canada’s political statements about Ukraine to respond positively. From a military point of view, the matter is more complex. Ukraine is in its own right an exporter of weapons and seems to have all that it needs to deal with the localised military conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Dealing with a large-scale Russian invasion would, at least in the view of some experts, require an increase in military capacity that it is impossible to achieve in the near future. The general conclusion is that beginning such a build-up at this stage is not good tactics and could even be counter productive. In that context, the current Canadian approach of providing training rather than weapons is, all things considered, a sensible one. It is useful in any event. It may not lead to immediate threat reduction, but it also does not ratchet up the tension level.

|

| President Zelenskyy receiving FM Joly, Kyiv, January 18th |

KAZAKHSTAN TOO

The protests

that affected Kazakhstan in early January have been described at the actions of

terrorists by President Tokayev. What began as a series of protests over the

sudden increase of gas prices turned into unusually violent demonstrations.

They even compelled the president to issue a shoot-to-kill order. He also invited

troops from the Collective Security Treaty Organization's to enter the country

and provide assistance to Kazakhstan security forces, but, it seems, mostly

outside of conflict areas. The call for outside assistance may have been a way of

securing the message that the President still had the full backing of Moscow

and that protesters should have no illusion about getting any eventual support from

Russia’s political or security establishment.

|

| President Kassim-Jomart Tokayev |

Foreign

observers are still struggling to find the right explanation for the events.

Most are still reeling from the fact that they did not see anything coming. There

was evidence of some dissatisfaction with the uneven distribution of wealth and

of animosity towards those who have become rich in the period since Kazakhstan

became independent, especially the Nazarbayev family. The stability seemed supported by a relatively good living

standard. The new President was in the process of implementing in a gradual

manner a moderate political reform process.

If the

causes of the protests still require clarification, the results have become

evident rather quickly. President Tokayev has already taken control of the

National Security Council from his predecessor during the crisis itself. He has

since firmed up his control of the government apparatus. He also has taken over

the leadership of the Nur Otan party that has the majority control of the

Parliament. He has called on those (including the family members of the former

President Nazarbayev) who have acquired considerable wealth to contribute back

to society as the same as obtaining explicit support from former President Nazarbayev.

He also has offered an ambitious economic reform agenda.

Now that the dust has settled, the government has also agreed to investigate human rights abuses that may have taken place during the protests.

The general impression

is that, as result of the tragic events of January, new impetus has been given to

a reform and modernisation process that enjoys broad popular support. Based on

the pronouncements of President Tokayev, optimism is justified. The only caveat

is the required acknowledgement by foreign observers that they failed to see

the protests coming and may not have a deep understanding of the many dimensions

of the political landscape in Kazakhstan, including the possible obstacles to President Tokayev's plans.

--o--

THE AUTHORS

Friday, December 31, 2021

BGN 59

HIGH-LEVEL RISK MANAGEMENT

THE GLOBAL CONTEXT

The

discussion in the media continues to focus on the movement of Russian troops in

the vicinity of Ukraine and the possible invasion of Ukraine it may prepare, as

well as on the sanctions against Russia this would produce. The December 30th

diplomatic discussions between Presidents Biden and Putin seem to have focused

much more on the matter of long-term security arrangements between the US/NATO

and Russia. The media focus on possible war rather than on possible peace keeps

the pressure on both sides to continue their discussion. This is important

especially for the US as there is probably neither a full understanding of

President Biden’s objectives nor full domestic or Euro-Atlantic support for the

negotiation process he has agreed to initiate with Russia. That process is

predicated on the pursuit of long-term objectives that may not be shared by the

US foreign policy establishment or by the countries of the so-called New Europe

such as Poland and the Baltic States. Some, even within the Biden

administration, would rather continue the policy of confrontation with Russia

and would object to anything that appears to reward rather than punish Russia.

Ever since

the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty ceased to be operational in July 2007

there has not been an arrangement that would define the terms of acceptable

military presence between Russia and, for all intents and purposes, the rest of

Europe. More recently, with the US withdrawal from the Intermediate Range

Nuclear Forces Treaty in August 2019, there has also been no framework for the

control of nuclear missiles in the European theater of operations.

There have

of course been attempts to fill the void, including the short-lived proposals

for a new European security architecture by then President Medvedev in June 2008.

Since then, with the war in Georgia in August 2008 and the conflict over Crimea

and Eastern Ukraine in 2014, the circumstances have not been conducive to

discussions on that theme. New START, the US-Russian treaty that limits the

number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads was, however, extended in 2021

for another five years.

What also

has become clear to Vladimir Putin the course of last year is that tension can

be creative. The movement of Russian troops closer to the Ukrainian border in

early 2021 fulfilled its expected purpose. The Ukrainian side got the message

that the Donbass was not going to be regained through military means. Bringing

the troops back to the Ukrainian border might create the tension that would

trigger US appetite for wide-ranging security discussions that have not really

happened for many years.

Under the

pressure of possible war in Ukraine, what Presidents Biden and Putin have

agreed to do is to start working on a new broad long-term security arrangement that would deal with the new alignment of forces in Europe. This is what Russia essentially proposed as early as in 2008. In the context of an ever-expanding NATO, the US did not see this as a priority, but may be willing to consider it now as a way to ensure stability while reducing its own military presence in Europe. On a personal note, Biden is old

enough, literally, to have been a first-row witness of all the major disarmament

treaties that were signed with the Soviet Union beginning with START in 1971.

He would be partial to that type of arrangement that could lessen the tension

between the US and Russia. Nowadays he would fully appreciate the fact that

this would allow him to focus more energy and attention to dealing with the

China threat. It might not detach Russia from China but would lessen the

prospect of a closer alliance between the two. Vladimir Putin publicising his

briefing of Chinese President after his conversation with Joe Biden was both a

reminder to Biden of what is at risk and to China that nothing will be done

behind its back.

As for Canada,

it would find it difficult not to support the Biden approach, but it may need

to produce a creative way of reconciling its unconditional support for Ukraine

with a process that appears to give less importance to the specific

Ukraine-Russia conflict.

--o--

THE UKRAINIAN CONTEXT

|

| President Zelenskyy, NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg NATO Headquarters, December 16th ©President of Ukraine Website |

What has

become clear to Russia in the past few months is that there is a threat of some

ersatz NATO membership for Ukraine in the form of a bilateral military

partnership between the US and Ukraine. The flood gates of NATO membership may

not open for Ukraine, but there could a creeping growth of US military presence

on Ukrainian territory in the form of increasingly more sophisticated military

equipment, well beyond Turkish drones and US Javelin missiles.

Joe Biden’s

acquiescence to the idea of security discussions with Russia may also be

consistent with his approach to the conflict in Afghanistan. The US should not extend

its presence or commitment in a case when no resolution is in in sight. Afgnanistan returned to the Taliban, but Ukraine will not return to Russia.

The

acquiescence to the discussions is also an indirect but clear acknowledgement

that the situation in Ukraine will not be resolved shortly and that, in any

event, it is not for Russia to make the next move. One should not expect that

this would be well received in Ukraine. This is not to say that the US will

stop supporting Ukraine or that the broad question of European security can eventually

be resolved without the specific question of Ukraine being resolved or at least

frozen in some acceptable way. It does however put some pressure on President

Zelenskyy if he wants to avert the risk of Ukraine’s lost territory becoming a

Cyprus-like frozen conflict.

Despite all

the care that the Biden administration has taken to assuage Ukrainian concerns,

it was only a matter of time before a political commentator would suggest that

Biden is betraying Ukraine. Ironically, it is Andrey Illarionov, a Russian

national, a former advisor of Vladimir Putin and one of his most vocal critics

who did it, in unequivocal terms: “Biden once again surrendered Ukraine. On all

issues that matter to her, he completely sided with Putin.”

The Kremlin

readout of the most recent Biden-Putin meeting also notes that President Biden

offered assurances that the US does not intend to deploy offensive weapons on

the territory of Ukraine. That would held clear the atmosphere of the upcoming US-Russia

negotiations but would once more disappoint the more hawkish elements in the US

and Ukraine.

What is not

covered thus far is what the US proposes to do with the Ukraine-Russia

confrontation. There is still an interest in resolving that conflict. There is

now a new truce in place in the Donbass area. It may last longer than previous

ones. Reducing militarisation in that region first might be a first step that

fits in the resolution of the global conflict. In order to enable Zelenskyy to

engage credibly in any peace discussions, he has to be seen as having gained a

stronger position both at home and vis-à-vis Russia. This is a tall order. A

complete cease-fire, the withdrawal of some Russian troops and possibly the commitment

to the presence of neutral peacekeepers might help.

--o--

THE NEGOTIATION

The Russian

idea of publicising the draft texts of treaty with the US and with NATO may

have appeared as rather unusual. The fact is that this is a negotiation that

will have to be transparent in any event given the number of participants and

the expected reluctance in some NATO quarters. Ultimately, public discussion

could facilitate the work of the leaders. Including a clause that would

preclude further eastward expansion of NATO (mostly Ukraine) allows all the

NATO spokespersons to posture and repeat their mantras about the unacceptability

of Russia deciding for NATO. As noted above, Presidents Biden and Putin already

know that Ukraine will not become a member of NATO in the near future. They

also know that an outright exclusion of NATO membership will never pass.

Renouncing that exclusion can, however, be presented as a Russian concession

whenever appropriate. In any event the real goal is to prevent NATO assets (missiles

and troops) from being too numerous and too close to Russia and equally for

Russian assets to be in comparable number and distance from all NATO countries

and NATO-aspiring countries.

|

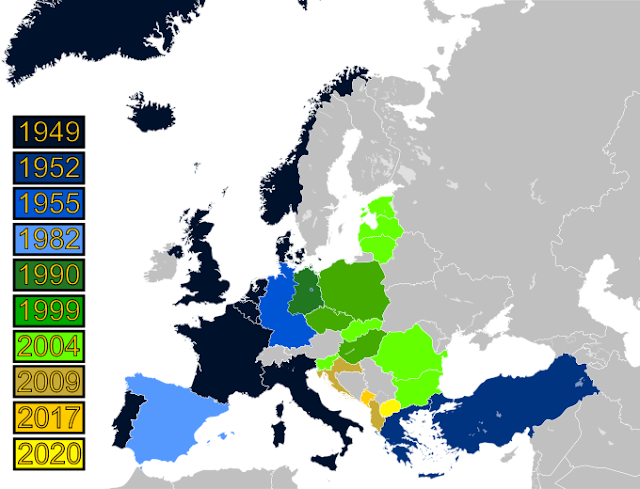

| Evolution of NATO in Europe ©Patrick Neil |

It has been observed that the staging of NATO missiles in the proximity of Russia would be as unacceptable to Russia as the staging of Soviet missiles on Cuba was unacceptable to the US in 1962. This gives a good sense of what has to be negotiated first. It should also be noted the deployment of US missiles is what is at stake, not any British or French ones, and that this would be exclusively a US decision no matter how much the Ukrainians may want them on their territory.

Finally, the staging of the upcoming discussions (US-Russia on January 10th, NATO-Russia on January12th and OSCE on January 13th) may not guarantee success but suggests that the process is carefully choreographed.UKRAINE: SCRAMBLING FOR SOLUTIONS

At a time when

the need for a strong president is felt more acutely, it looks as though President

Zelenskyy has reached his lowest popularity level. His attempts to buttress his

nationalist credentials with some anti-Russia trade measures or to appear as a

strong leader by allowing for the prosecution of his predecessor, former

President Poroshenko, are unlikely to have much positive effect. Zelenskyy is

of course coming under all forms of attack from political adversaries but also

receives the occasional indirect criticism from the US Embassy for, as an

example, the appointment of a key anticorruption official.

|

| President Zelenskyy visiting the Donbass frontlines, December 6th ©President of Ukraine Website |

The latest

attack from a former Interior Minister is that the Putin administration disposes

of compromising material against Zelenskyy. That would seem far-fetched but is

revealing of the current atmosphere.

The fact that

Zelenskyy was perhaps the only leader not to have received New Year’s greetings

from Vladimir Putin would normally have been a badge of honour but seems to

have had no positive effect on Zelenskyy’s standing. More timely calls from Joe

Biden would probably have been useful. In the context of the current US-Russia conversations,

the question remains as to whether Zelenskyy is part of the problem or can

become part of the solution.

--o--

MEMORIAL, THE SAKHAROV LEGACY

Memorial,

the human rights NGO whose work includes researching and keeping the memory of

past repressions in the USSR and current repression in Russia, was shut down on

December 28th by a decision of the Russian Supreme Court. That decision can be

explained in legal terms on account of the restrictive Russian legislation on

foreign agents. The decision to prosecute may not have been only based on an

attempt to deny the repression of the Stalin era but as well to quell a

dissenting voice in the interpretation of historical and current events. The

nuance is important in the context of a society that no longer has the likes of

Andrey Sakharov and, as a result, has few widely respected and authoritative

dissenting voices.

--o--

THE AUTHORS

Thursday, December 2, 2021

ISSUE 58

THE BRETON/GEROL NEWSLETTER

UKRAINE UNDER ATTACK?

The

international discussion about the movement of Russian troops within Russia

itself and how it might presage a possible invasion of Ukraine by Russia has

certain elements of déjà vu. Earlier in 2021 Russia moved troops close

to the border with Ukraine, probably even closer than they are now. There was

not so much speculation then about a full-fledged Russian invasion. The

incident faded away and many of us were able to conclude that Russia had

responded to Ukrainian moves around the rebel regions of Eastern Ukraine by

sending a message to Kyiv about the military reaction that could be expected

should Ukraine be tempted to follow the recent Azerbaijan example. (In the fall

of 2020 Azerbaijan used military force to regain control of a part of its internationally

recognized territory in the Karabakh region.) The early 2021 events around

Eastern Ukraine were then followed by high-level meetings including the first Biden-Putin

summit and a period of relative quiet.

Things are different

this time around. On the previous occasion, Dmitry Kozak, the Russian

presidential administration point man on Ukraine stated unequivocally that a

Ukrainian offensive on the rebel regions would lead “to the end of the Ukrainian

state in its current form.” This time the interpretation of military

movements has been that there was no pre-condition and that Russia was

considering invading the whole of Ukraine. Some commentators have speculated

that for Putin Ukraine remains the unresolved conflict of his presidency and

that as he moves along in years, he may be inclined to consider more radical

measures. There has also been some reference to Putin’s statements about Russian’s

red lines and about tensions being useful to get the attention of the other

side.

Does Russia really contemplate invading Ukraine? If one looks at the question from the point of view of Russian national interests, the answer is an obvious no in virtually every respect. Does Vladimir Putin contemplate invading Ukraine? To give that answer Putin turned to his long-term associate Sergey Naryshkin, the head of the Foreign Intelligence Service (Russian acronym: SVR), to re-state that Russia has no intention to invade Ukraine. In the response to the claim of an unusual presence of troops near the border the Russian authorities had earlier chosen to use the SVR as the agency to rebuff the claims of an unusual presence of troops. The SVR statement even compared what it called a US propaganda exercise as something taken from Goebbels’ book, no less.

When it was

made earlier this year, the above-mentioned Kozak statement was not understood

to imply an invasion of Ukraine but rather a strong military and political

response to any attempt by Kyiv to recover through military action the rebel

territories of Eastern Ukraine. The conditional aspect was clear. What it also

made clear is that Putin would not consider ever abandoning the

Russian-speaking populations of Eastern Ukraine.

The one

leader who seems to have understood the situation clearly and said so is

President Zelenskyy. During his late November marathon press conference, he did

not deny the risk of war but criticized alarmists for predicting imminent open

armed confrontation. He nevertheless emphasised that Ukraine is now much more

ready to defend itself than it was a few years ago. “We have been at war for

eight years. And the likelihood of large-scale or continuation of a strong

escalation by Russia or militants backed by the Russian Federation may take

place any day. But I think that today there is intimidation from some sites and

media that there will be a war tomorrow.”

Zelenskky

has perfectly understood the meaning and extent of the Russian threat. He is

the person who could trigger that threat by ordering military action to retake

the rebel regions. That would be running against everything that he has said

since he became president. To this day, he keeps emphasising that he wants to

negotiate, but from a position of strength: “we will not be able to stop the

war and return the territories without our troops and without direct talks with

Russia.”

As for NATO

countries, they have no choice but to denounce the Russian threat and in turn

threaten of serious consequences, even though not extending to direct military actions. This will not put Russia on the defensive but

will justify increasing military assistance to Ukraine. The US is using the

same strong rhetoric but without going too far. Ahead of his own meeting with Foreign

Minister Lavrov, Secretary of State Blinken was edging his bets on the

likelihood of an imminent invasion, so as not to prevent the organisation of

another Biden-Putin conversation later this year.

|

| Secretary of State Blinken and Foreign Minister Lavrov Stockholm, December 2nd |

As for

Russia, it has no expectation from Ukraine, but may not have given up on NATO

countries. A credible threat may have been enough to trigger the launch of

discussions on long-term security guarantees between Russia and NATO, as seems

to be suggested by Russia’s publicly expressed hopes on the agenda for the upcoming

Biden-Putin virtual meeting. This is not the same as excluding Ukraine from NATO

membership for ever. It goes back to the fundamental long-term issue of staging

and deployment of military assets. It does not imply less support for Ukraine

from the NATO side. It would imply, however, the acknowledgement that the

Ukraine conflict itself will not be resolved any time soon as well as that Ukraine has

so “separated” itself from Russia that it is no longer as crucial as it was seen during Colin Powell’s time as Secretary of State. Frustration and anger emanating

from Kyiv could be expected and did not fail to materialize. It should be understood though that this is a long-term discussion that will not alter the current US rhetoric, may run into political

obstacles and would unfold slowly in any event.

--o--

NEGOTIATIONS, WHAT NEGOTIATIONS?

Behind the discussion

about the possible Russian invasion of Russia, there have been political and

military developments that have set the stage for the current level of public

confrontation.

Politically, there has been pressure on Russia to convene another

meeting of the Normandy Four (Ukraine, France, Germany, and Russia). The story

went on that President Putin had agreed to this under pressure from President

Macron and Chancellor Merkel but that, according to French and German sources,

Foreign Minister Lavrov was balking. This led Lavrov to take the highly unusual

step of publishing the full text of his correspondence with his French and

German counterparts. This was intended to clarify the Russian position that Putin

had agreed to ask Lavrov to try to organise a meeting, but that the Russian

conclusion is that there is no point in another meeting of the Normandy Four as

this time. The main reason is that there has been no progress on the

implementation of the decisions of the previous meeting, specifically Ukraine

making no progress toward the implementation of the Minsk Agreements (that

establish the principles for a settlement of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine).

After many years of Ukraine supporters parroting the line that Russia needs to

abide by the Minsk Agreements, there is now subdued recognition among diplomatic observers

that it is Ukraine that has a fundamental problem with these arrangements.

|

| President Zelenskyy addressing the Rada December 1st, Kyiv ©President of Ukraine Website |

Things are

also different on the military front. Ukraine has begun to use its Turkish-made drones in

Eastern Ukraine, it also apparently used US-provided Javelin missiles and,

using the cover of both, it has according to Russian sources brought its troops

closer to the confrontation line. The UK sent a military ship to the Black Sea

to test the limits of what might be legally and operationally possible. The US

has also sent strategic bombers in the vicinity of Crimea. NATO countries also have

assessed the limits of Russian preparedness in the Black Sea, in the vicinity

of Ukraine. Poking the bear is the comparison that comes to mind.

There have been

indications to Ukraine that it would not be allowed to join NATO anytime soon.

There has however been increasing US and other support for the Ukrainian military

that, for its part, has been constantly improving its capacity and performance.

|

| President Zelenskyy recognizing a Ukrainian veteran December 1st, Kyiv ©President of Ukraine Website |

Things have

also changed in Ukraine proper. The Zelenskyy administration has allowed the

passage of legislation that does not include ethnic Russians as native people

of Ukraine. It is also preparing legislation that, in Moscow’s view, is equivalent

to withdrawing from the Minsk Agreements.

More

important though is the message that Russia has essentially given up on

Zelenskky as a political leader who could resolve the Eastern Ukraine problem.

Ukrainian public opinion will not support the implementation of the Minsk

Agreements. Zelenskyy has neither really tried to change nor offered the beginning

of a workable alternative solution.

The offer

of President Erdogan of Turkey to mediate the conflict between Ukraine and

Russia was not taken seriously and was most likely seen as the product of a

mind that has an over-inflated idea of its importance. As France and Germany

have failed, others should perhaps be inspired by the offer and come forward.

As it is, there is no sign of any possibility of progress in the foreseeable

future. As noted above, Zelenskyy’s call for direct talks with Russia will elicit

no response.

--o--

LUKASHENKO, AS A PASSEUR

Alexander

Lukashenko has acted in a way that puts him in the same category as the passeurs

who take advantage of refugees and charge them large amounts of money to take

them across the English Channel. Lukashenko did not do it for money of course,

but for some eventual political advantage in the form of some sort of de

facto recognition from the EU. The most likely inspiration, though, for his

actions is that he probably wanted to seek vindication against the Polish

authorities. Lukashenko seems to have enjoyed exposing what he sees as the double

standards of the Polish government that rushed to offer political asylum to

Belarus opposition figures but would turn back asylum-seekers from the Middle

East. He would also have enjoyed the irony of the proposal to fly the

asylum-seekers directly to Germany, an idea that would throw further light on

the discrepancy between the Polish and German approaches to refugee issues. The

fact that the asylum-seekers are leaving their home countries as a result of

failed US/NATO policies would just have been an extra source of satisfaction.

Lukashenko’s

utter disregard for the life and well-being of the refugees obviously meant he

could not avoid well-founded criticism. Sacrificing a few people did not matter

to him.

Chancellor

Merkel, in her end of reign caretaker capacity agreed to speak directly to

Lukashenko to achieve a resolution of the problem. Rather than receiving due

gratitude, Merkel is now being criticized by the Polish Prime Minister for offering

recognition to an illegitimate dictator. The German side is strongly denying

this is the case.

Lukashenko’s

dumping of refugees on the border with Poland was such a blatant provocation

that the Polish side did not suffer too much reputational damage for its hard-line

refugee policy. The whole incident, however, gives comfort to other EU

countries such as Hungary that harbour policies like that of Poland. It illustrates policy

differences among European countries at a time when France and the UK are

confronted with serious challenges in this area.

Lukashenko

may not have won much in all of this other than to reinforce his image at home

and in the neighbourhood as a strong Soviet-era leader, the so-called cunning

peasant, and one who does not care much about a few lost lives.

--o--

ZELENSKYY’S PRESS CONFERENCE

From

Zelenskyy’s end of November marathon press-conference the item that got the most attention was

his allegation that a coup d’état against him was under preparation for early

December by unspecified individuals from Ukraine and Russia. He mentioned oligarch

Rinat Akhmetov as one who may have been played by the alleged conspirators. The

expected denial of any such conspiracy from all possible sources quickly

followed.

Ukrainian

oligarchs would certainly have no love for Zelenskyy and his attempts to

de-oligarchise the Ukrainian economy. Conversations they may have had about

Zelenskyy would most likely have included some rather unpleasant remarks

directed at the President. Oligarchs do however still have a lot of tools at

their disposal, including the media, to undermine Zelenskky other than a coup d’état.

Wittingly

or not, Zelenskyy’s remark about a coup briefly shifted public attention from a Russian

threat to Ukraine to a rather vaguely defined threat against himself. One of

his problems has always been the perception that he is not strong enough to

face Vladimir Putin or to reign in the oligarchs. Presenting himself as one who

can overcome attempts is always useful.

--o--

ZELENSKYY’S RECORD

As could be

expected in the case of a President who has been in power for more than two

years, a lengthy unscripted press conference will lead to the airing of alleged

mistakes, scandals, or disputes. Zelenskky now has plenty of accusations to

contend with in this respect, some of which are not warranted at all. The most

significant attack against his policies came from an unlikely source, an

article in the Atlantic Council. The title says it all: “Ukraine’s

anti-oligarch law could make President Zelenskyy too powerful.” The article essentially criticizes the

President for his continuing links with oligarchs as well as the new

legislation concentrating too much power in the presidential office. The

substance of the article may not matter so much as the fact that an entity that

is expected to be pro-Ukraine should publish an article that is critical of the

President, thus confirming a misalignment between Zelenskky and some pro-Ukraine

voices.

By

contrast, looking at presidential activity since Zelenskyy’s accession to power,

it might be equally noteworthy that the government procurement methodology

that is currently in place has been supporting the rather successful

implementation of the President’s "big construction" program. By doing away with

the level of corruption that so prevailed especially during the Yanukovych

presidency, the Ukrainian governments seems to have been able to devote

resources to infrastructure projects that will support the modernisation of the

country. The long-term impact will be significant.

The other

project that deserves mentioning is the revival of the Ukrainian aircraft

industry on the basis of the Antonov aircraft plant as well as the

modernisation of the air transport infrastructure. In the context of a

continuing pandemic, and despite the priority seemingly given to cargo

aircraft, the timing of the announcement may surprise. The long-term view is nevertheless laudable. There was yet no indication of a Canadian connection to this project.

--o--

THE TALIBAN AND CENTRAL ASIA

As the US

and the Taliban prepare for their first consultations since the US dropped out

of Afghanistan, a few observations are in order.

Many

explanations have been given for the quick takeover of Afghanistan by the

Taliban. The Taliban have received credit for their proximity to the people.

The outgoing authorities have been blamed for their corruption and in some

regions for their authoritarian conduct. Ethnic and tribal factors have been

mentioned. There has however not been a fundamental acknowledgement that the US

and NATO policies were flawed. There however has been some outside

acknowledgement of the immoral aspect of the US and NATO abandoning their

supporters and their civil society allies.

In the

discussions with the Taliban, the US will be expected to insist on the necessary

inclusiveness of new Afghanistan government if it wants to receive

international recognition and gain access to the country’s financial reserves

kept by international institutions. The question arises as to how far the US is

ready to go to withhold funds that are now needed for humanitarian purposes.

John Bolton, briefly Trump’s national security advisor and one of the supporters of the flawed US policy in Afghanistan, recently claimed that with the US departure Afghanistan would soon become the source of terrorist attacks against US interests. In this case, reiterating past assumptions implies not being even close to acknowledging mistakes.

There has also been the idea that the Taliban could be supported to squeeze out ISIS-K, considered as a distinct radical terrorist entity. That may be a way for both sides to save face, if the Taliban can be convinced to go after their Muslim brothers.

In dealing with Afghanistan, the US seems to have tried to exercise some influence over Pakistan, with little success. Other than that, the US seems to have held the view that they could deal with Afghanistan on their own. There may have been little appetite to deal with Russia, Iran or China. Relatively little attention would have been paid to Central Asian countries.

It is worth

noting that it is mostly Uzbekistan that supplies electric power to the city of

Kabul, to this day, on humanitarian grounds, even if the Afghan side is not able

to pay. The Uzbek Foreign Minister was the first foreign official to visit

Kabul. Uzbekistan and the Taliban have now already agreed on Uzbekistan

re-building the Mazar-i-Sharif airport.

For its

part, Russia has already started sending humanitarian shipments to Afghanistan and flying back to Russia Afghan students that are registered in Russian universities.

There is no

sign yet that US could acknowledge that it might achieve its own objectives in Afghanistan by cooperating with the other governments of the region.

--o--

NAGORNO-KARABAKH

It would

look as though Vladimir Putin not only managed to sit the President of

Azerbaijan and the Prime Minister of Armenia in the same room on November 26th,

but also managed to achieve results on three main topics of discussion.

|

| Presidents Aliev and Putin, PM Pashinyan Sochi, November 26th © President of Russia Website |

On the delimitation

of the boundary between Armenia and Azerbaijan, it looked as though Azerbaijan

was hoping to extract further concessions from Armenia prior to agreeing to the

formal process of delimitation. Delimitation would be crucial to avoid further

armed skirmishes on the confrontation lines. The results are not immediately

visible, but the process should be launched before the end of the year.

Humanitarian

issues: this is mostly about returning home the prisoners held by both sides.

It would seem that there are more Armenians to be returned than Azerbaijanis.

There is no specific deadline but a general expectation of early movement.

Re-opening

of economic corridors: this goes beyond just stopping

the fighting. Re-establishing the functioning of land transport is a vital

long-term economic requirement that can bring changes to the region.

The general

sense is that Armenia got more on boundary delimitation and humanitarian issues

than Azerbaijan had hitherto been willing to concede. What leverage Putin was

able to use on Aliev is not entirely clear but may become evident in coming

weeks as the implementation of decision unfolds. There may have been a discrete

but decisive role for Turkey in this process.

Economic

corridors matter to all, including Russia, but Armenia would probably stand to

gain more in the short term.

--o--

GAS PRICES IN EUROPE, UPDATE

In the

seemingly endless debate around the completion and now the legal certification

of Nord Stream 2, a short mid-November news item seems to have gone largely

unnoticed. As the German authorities announced there would be delay in legal

certification, gas prices in Europe jumped by 10% in one day. That should speed

up the process of using a pipeline that is now fully completed. Yet Ukraine and

the UK, obviously not having to foot the bill, are still fighting against Nord

Stream 2, as a matter of principle. Fact that they are also driving up the

price for one of Russia’s main commodity exports also seems not to matter.

--o--

THE AUTHORS

Monday, November 1, 2021

ISSUE 57

THE BRETON/GEROL NEWSLETTER

NATO-RUSSIA: MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING

In early October, NATO expelled eight Russian military officials working at Russia’s Representation to NATO. In response Russia closed its representation to NATO and NATO’s Information Office in Moscow. Even in a quiet month for relations between Euro-Atlantic countries and Russia, this is almost a non-event as NATO-Russia relations have been reduced to virtually nothing over the last seven years since the Ukrainian crisis. NATO’s actions were founded on "an increase in Russian malign activity, and hence the need for greater vigilance. A NATO official said the individuals were "undeclared Russian intelligence officers". There is some unrecognized irony in this. If you are a Russian official at NATO and you can only have limited official contacts with your counterparts, there is not much left to do other than to try to collect intelligence. In any event you would report directly to the Intelligence group at your Ministry of Defence as all military attachés around the world do on a regular basis. In a limited interaction context, if you cannot collect intelligence, one might even ask what is the point of a representation?

|

| NATO Secretary General Rasmussen, President Putin, NATO-Russia Summit, Rome, May 2002 ©NATO Website |

In an ideal

world, the situation in Afghanistan when the US decided to enter the country in

2001 could have been an occasion for NATO-Russia cooperation. This is not to

say that the outcome would have been different. That which can be observed

though is that in and around 2001 the US and NATO had the option, in support of

their Afghan operations, to operate bases in Central Asia with the acquiescence

of Russia. Nowadays Russia openly calls on Afghanistan's neighbours to refuse

to host U.S. or NATO military forces following their withdrawal from

Afghanistan. This may not be so significant in strategic terms, but in terms of

NATO/Russia cooperation that step backward is far more significant than closing

the NATO Information Office in Moscow. It also confirms that nothing much can

be expected on the NATO-Russia front for the near future.

--o--

THE LESS KNOWN COLIN POWELL

NATO

The brief

return of NATO to the headlines around the time of the passing of former

Secretary of State Colin Powell is the occasion to take another look at NATO,

starting with some private but not so secret observations that Colin Powell himself

made about his NATO experience. Powell was known to have observed that one of

the NATO ministerial meetings in which he had to participate was probably the

worst meeting he ever attended. These observations were relatively private and

do not amount to calling the organisation brain-dead as President Macron did 20

years later, but they reflect a frustration with the lifeless political

conversation within NATO.

It should

be understood that the criticism directed at NATO really focuses on the

Alliance’s stultified political function. It should also be acknowledged that,

to many members, having a politically brain-dead institution is desirable, as

they see no need for creativity or change. This also explains the inherent lack

of interest for a NATO-Russia Council that could have changed the terms of the

relationship with Russia.

The

commitment to NATO on the part of founding members as well on the part of

Eastern European countries who wanted so badly to join after the end of the

Cold War is really based on the mutual defence commitment embodied in article 5

of the Washington Treaty. The collective defence arrangements that follow from

this commitment are really what matters. Among newer NATO members, there is

little or no appetite for change. There is also little enthusiasm for a purely

European defence arrangement.

UKRAINE

One of the

other private comments made by Colin Powell during his tenure as Secretary of

State in the early 2000s was that the next battlefront with Russia would be

Ukraine. This was before any Orange Revolution. This was Powell’s straightforward

and prescient acknowledgement that Russia’s attempts either to re-build the

Soviet Union with Ukraine inside or even to keep Ukraine in its zone of

influence would be met with resistance on the part of the US and most likely as

well, some of the new members of NATO, especially Poland and the Baltic states.

The comment had the merit of clarity to the effect that the primary concern was

to counter Russia.

On a

separate but related front Dimitry Trenin, the Director of the Carnegie Office

in Moscow, recently reported that Russia would have wanted to expand the

Normandy Four (Ukraine, France, Germany, Russia) discussions to include the US,

acknowledging that the US has the most influence on Ukraine. This was also a

Ukrainian suggestion. France and Germany objected as it would lessen their role

and not necessarily lead to any resolution of the conflict with the US having

little incentive to normalise the Ukraine-Russia relationship.

--o--

THE

EUROPEAN GAS CRISIS

There have

been contradictory analyses and statements about the role of Russia in the

current European gas crisis during which prices have increased three times in

some cases. Prices went down 20 % after Russia announced in late October its

intention to increase exports. Some have credibly explained that Russia is not

responsible, with many other factors including the weather causing the current

problems. Since it is clear that, with German approval, the Nord Stream 2 will

soon become operational, the idea that Russia was withholding gas to secure

some other form of approval for the pipeline did not seem to be widely believed.

Others have argued that Russia’s reputation as a dependable supplier suffered.

Giving itself the good role, Ukraine

offered to arrange for the transit at a reduced rate of more Russian gas

to Western Europe. Others have even argued that Russia’s insistence on

long-term contracts contradicts the objective of moving away from fossil fuels.

Chancellor Merkel corrected the copy by clarifying that the initial necessary

transition is from coal to natural gas.

The above-noted

turmoil in the European gas market would seem to suggest that Chancellor Merkel

was quite right in supporting the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline

that will bring Russian gas to Germany through a pipeline on the floor of the Baltic

Sea. It will avoid land crossings and the attending transit fees; it will

diversify the pipeline grid and it will use a more modern and more reliable

technology than Soviet-era pipelines.

|

| Nord Stream 2 at Russian landfall |

Ultimately,

for the foreseeable future, there is mutual dependence and convergence of

interests between Russia, the largest provider and Germany, the largest

customer: long-term, stable, and secure sales and supplies. The EU, the US and

transit states have different concerns, but they do not alter this fundamental

element.

In an early

November last-minute attempt to prevent the approval of Nord Stream 2, the head

of Naftogaz, the Ukrainian State Gaz company, added to the usual geopolitical

arguments the observation that the end of the transit of Russian gas through

Ukraine makes the prospect of open war between the two countries more likely.

Theoretically, he may be right. The rather excessive nature of the remark

limits its usefulness but illustrates the state of mind in some parts of

Ukraine.

--o--

UKRAINE UPDATE

The late

October use of a Turkish-made drone by Ukrainian Armed Forces against Eastern

Ukraine insurgent forces has caught considerable attention and even elicited

critical comments from France and Germany. No such criticism came from the US.

There is a sense that, as the situation in Eastern Ukraine generally stagnates,

President Zelenskyy may be inclined to turn to an increase of military

activity, especially if that activity is conducted on a remote basis that

avoids new casualties on the Ukrainian side. In political terms Zelenskyy has

little choice but to show a stronger positionvis-à-vis Russia. This may sustain his popularity,but may not achieve anything else.

--o--

VACCINES IN RUSSIA

Questions

have been repeatedly raised about why Russians do not get vaccinated and

whether this is a rejection of Vladimir Putin and his policies.

The first

question has received a fairly credible answer from public opinion experts.

When it comes to vaccines, the Russian experience was shaped by the mandatory

vaccine policy implemented by the Soviet bureaucracy. The end of the USSR and

individuals regaining their personal space have meant that people are

protective of their freedom of choice when it comes to things that were in the

past imposed from above. The fact that vaccines served to eradicate some

diseases does not seem enough to counter that tendency.

When it

comes to vaccine and leadership, a possible explanation may be that the

situation is most likely complicated by the way Russians receive official

information and how this is to a considerable extent separate from approval of

leaders. Anything that falls into the category of messages that are intended to

influence opinion (what used to be called propaganda) tends to be automatically

discounted and read at a different level. In other words, the fact that you are

popular does not mean that I believe everything you say especially if you are

trying to tell me what to do.

Incidentally,

with vaccines perhaps not so readily available in neighbouring Ukraine, by the

end of October the vaccination rate there would seem only be at 24% compared to

Russia’s 38 %. Some of the same vaccination reluctance may extend beyond

Russia’s border for reasons that are not dissimilar.

--o--

VALDAI CLUB NEWS

President

Putin’s speech at this year’s mid-October meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club argued

that Russia’s development should be founded on a “conservatism for optimists.” The speech may offer a picture of a Putin that is less extreme than is generally perceived. What is more striking though is that the speech is at a philosophical level that virtually no

one would ever expect from a North American leader. This is the kind of speech

that Merkel or Macron might do on special occasions. It may not and should not change your

opinion of Putin as an authoritarian leader, but it is revealing of the Russian

political culture that the President sees the need to engage in such a discussion.

|

| President Putin and discussion moderator Fedor Lukyanov, Sochi, October 21 ©President of Russia Website |

Another

less widely publicised element of this year’s Valdai Club meeting was the

attendance of the most recent co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, Russian

journalist Dmitry Muratov. To Western observers this may have looked rather

unusual. A person who is presented as an anti-establishment journalist and a

defender of freedom of speech not only gets invited but engages in a public

conversation with the President about the vexed question of foreign agents. You may not have a choice if the President

invites you, but if he invites you, he signals to the rest of the establishment

that you are under his roof. This is also revealing of a slightly more complex

political environment than is generally described in Western media.

--o--

RUSSIA AND CHINA: PACTA SUNT SERVANDA?

As many

political analysts are trying to devise what might be a new China policy for

the US and for Canada, there is a temptation to find points of comparison

between the way the West dealt with the USSR/Russia and the way it should deal

with China.

This also

has some bearing on the ongoing academic debate about whether Russia is on a

convergence or divergence path with Europe.

Without

going into a long academic discussion, we would single out a major difference:

throughout the difficulties of relations between the Euro-Atlantic community

and Russia it was clear that Russia wanted to be a member of the club or, as

some put it more crudely, join the civilised world. Ukraine became a turning

point in that there was a major collision between the interests of Russia and

the interests of the Euro-Atlantic community. There is fundamental disagreement

as to whether rules were followed. Russia essentially rejected the Western

interpretation of how the rules of international law should be applied. In

engaging in the Minsk Peace Process, Russia nevertheless confirmed its

intention to have at least part of the problem resolved through diplomatic

negotiations.

In the case

of China, issues such as the ill-treatment of the Uighur minority or the

prolonged unfounded detention of two Canadians are important, but none is more

indicative of China’s state of mind than its current Hong Kong policy. China

has no intention whatsoever of abiding by the terms of the agreement with the

United Kingdom that led to the return of the territory to China. Neither the

United Kingdom nor any of its allies has any leverage to change that. Unlike

Russia, China is a club in itself. You would not hear a Chinese leader at any

level suggest that China wants to join the civilised world. When it comes to

matters of civilisation, China does not see the need to join what it probably

sees as a lesser form of life.

The other

main difference is that there never was between the West and Russia the kind of

economic relationship that currently exists between China and other major

economic entities.

Another

difference is that Russia may seek to use its diaspora for improving relations

whereas China seeks to control its diaspora to advance its interests. The

nuance is important.

The policy

of engagement with Russia hit the wall in Ukraine. With China, the priority was

always economic interaction. There are no major lessons to draw from our

relations with Russia we could apply to China other than that it should be quite

different as we are confronted with a global power that will interpret the

rules as it sees fit and a major client over which we have virtually no

influence or leverage.

--o--

THE MOLDOVAN EXCEPTION

In late

October, the European Union accused Russia of using gas to bully Moldova, the

small, former Soviet republic and, as the BBC called it to make it a bit more

dramatic, the poorest country in Europe. Within days, on October 29th, Russia's

Gazprom and the Moldovan government signed a new five-year contract for Russian

gas supplies on “mutually beneficial terms”. This is not

surprising. By force of habit, the EU had opted to blame Russia when the gas

contract negotiations were difficult. Granted, the discussions were complicated

with the European gas market being in turmoil and the two parties having to

deal with the gas supply to Moldova’s Russian-supported breakaway region of

Transdniestria. The EU reading of the situation did not, however, consider that

Maia Sandu, the pro-European President of Moldova seems to have astutely

created a very good working relationship with Dimitry Kozak, the Deputy Head of

the Russian Presidential Administration and a very long-time associate of

Vladimir Putin. To her credit, Ms. Sandu’s pro-Europe preferences did not

prevent her from creating the circumstances for advancing Moldova’s interest in

relation with Russia in a constructive manner. Politically she is in a win-win

position. Moldova is not Ukraine, but this may warrant re-considering the usual

assumptions about the incompatibility of good relations with both the EU and

Russia.

|

| August 11 meeting between Dmitry Kozak and President Sandu, Chisinau |

--o--

THE END OF THE ROAD FOR MISHA?

Mikheil

Saakashvili, former President of Georgia and former senior official in Ukraine,

returned to his home country in early October and called on his supporters to

march on the capital. He stands in opposition to the Georgian Dream party that

currently holds power in Georgia. He was imprisoned almost immediately on the

basis criminal charges against him going back to 2014. He has now undertaken a

hunger strike. Saakashvili can claim substantial reform achievements from his

time as President of Georgia (2004-2013), but also displayed

authoritarian tendencies that are behind the criminal accusations against him.

Russia holds him responsible for starting the 2008 Georgia-Russia war. Worse

though is that many Georgians hold him responsible for losing the war. His impulsive

style and egocentric tendencies have not always served him well and have not

made him many friends. In response to calls for the hunger-striking Saakashvili

to be moved from prison to hospital Georgian Prime Minister Garibashvili simply

said that Saakashvili “has the right to commit suicide.”

--o--

On October

24th Uzbekistan incumbent President Shavkat Mirziyoyev won a second

term with a majority 80% of the vote. Credible international observers from the

OSCE suitably acknowledged the reforms conducted so far by the President, but

also singled out a number of deficiencies. This is a classic case of observers

having to balance support for reforms with the continuing existence of legal

shortcomings. Perhaps more remarkable however was the fact that, after the

election, President Mirziyoyev received the head of the OSCE Observation

Mission. This is not a customary practice. Acknowledging the work of the

Observation Mission is not only a goodwill message to the Mission itself but it

is also a message to the political establishment about the validity of the critical conclusions of the Mission.

--o--

UNWANTED AMBASSADORS

President

Erdogan’s decision to declare a number of foreign Ambassadors (Including the

Canadian one) persona non grata over their criticism of his treatment of businessperson

and philanthropist Osman Kavala, jailed in 2017 despite not having been

convicted of a crime, was excessive even for an impulsive leader like him. His

reversal of the decision was a confirmation of the erratic nature of his

behaviour. Erdogan’s subsequent meeting with President Biden on the margins of

the G20 meeting in Rome “was held in a positive atmosphere”. What this might

mean is that Erdogan does not begrudge the Biden administration for what he saw

as the US support to the July 2016 failed military coup against him. With the acquisition

of an advanced Russian missile system still on track and with the supply of

American F-16 fighter aircraft still not resolved, it does not however signal a

significant turnaround in US-Turkey relations.

--o--